Introduction

In my previous blog, I touched on how I’d begun to adopt ‘pedagogies of affect’ (Kirk, 2010, 2021; Casey & Kirk, 2021) in my PE curriculum. This was a response to the wider learning experiences required of the Health and Well-being AOLE, but also in recognition that my previous approach to Physical education lacked a positive impact on the affective domain for students other than those already hooked on sport. I’d previously identified that my ‘traditional’ approach to PE was not working, and this would be even more apparent should I persist with it during the rollout of the new Curriculum for Wales. However, having digested @imsporticus blog ‘Traditions, not traditional’, I’ve probably mislabeled my previous approach. It wasn’t ‘traditional’ PE at all; it was just questionable practice through the enforcement of my own traditions. No matter the ‘what’ and ‘how’ of your curriculum and pedagogy decisions, it’s simply bad practise if it isn’t informed by and aligned with, the ‘who’ and ‘why’ in your context. Good practise in one context may very well be bad practise in another if it is simply duplicated and adopted. The Curriculum for Wales should be pushing PE leaders to reassess their purpose and curriculum within their setting.

Breaking away from traditions that hold us back

Within this blog, I aim to provide an example of how PE might look for those teachers in Wales who are vexed by the absence of detail in the AOLE What Matters Statements. With every school responsible for its own bespoke curriculum, some may interpret the learning experiences that could be provided in the progression steps as carte blanche to continue enforcing their own traditions of PE, but I implore you – don’t. Take this national opportunity to reflect and consider: “Are my traditions best for me, or best for my learners?”. Learning involves being uncomfortable – slipping into the learning pit – and the dominance and perpetuation of the sports technique-driven curriculum, in its tidy 6-lesson blocks, could be interpreted as the epitome of a PE teacher staying in the comfort zone. By simply looking at Wales’ performance in the Global Matrix 4 study compared to other countries, it’s objectively difficult to justify persisting with the status quo of those established traditions. Wales’ performance compared to other countries makes for some bleak reading. Sit down and…enjoy! PE provision doesn’t have all the answers to national movement tendencies and behaviours, but PE provision that doesn’t influence the affective domain positively in all students is most certainly a part of the problem.

Moving forward, do I have all the answers? Absolutely not. Might you disagree with my approach? Very possibly. But Stolz (2014, cited in @imsporticus, 2023) provides the notion that PE will always be contested due to its dynamic nature and will be “forever evolving in its pursuit to understand what physical is and ought to be and what physical education is.” That being recognised, I too will probably argue with my current approach in the next few years as my new traditions are formed and my setting evolves. However, I am delighted that I have colleagues such as Matthew Trowbridge and Ben King, both Heads of PE in schools close to my own, who are also keen to approach things in markedly different ways without fear of failure. Both characters are critical friends in my pedagogical decision-making processes. Promisingly, changes in my approach have led to increased physical competence, positive social experiences, and improved attitudes towards physical activity. This can only be positive for students in the short and long term of their capacity to engage in promoting their health and wellbeing.

Addressing the What Matters Statements within PE Lessons.

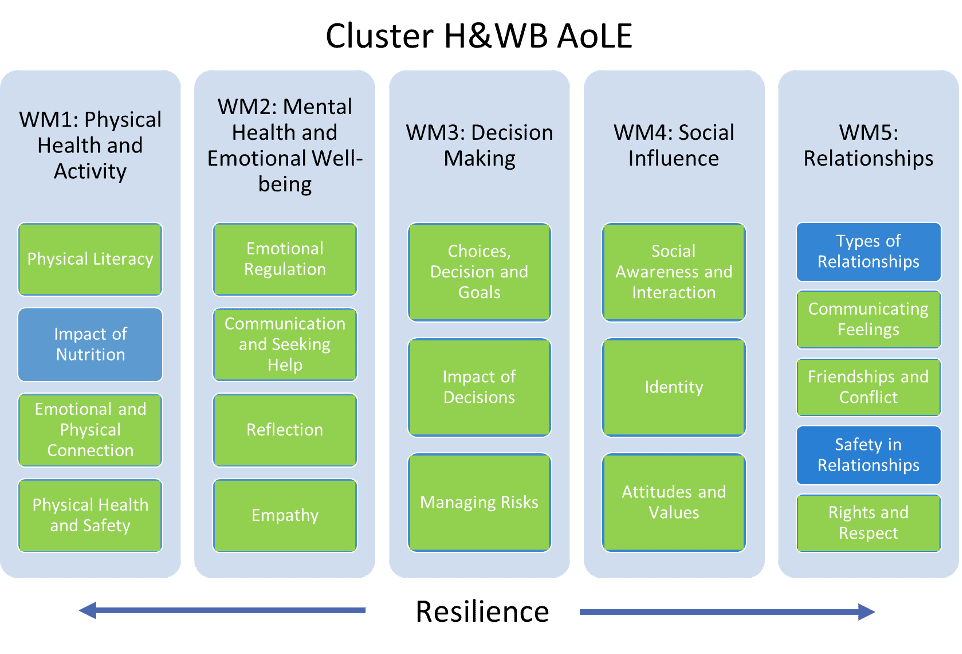

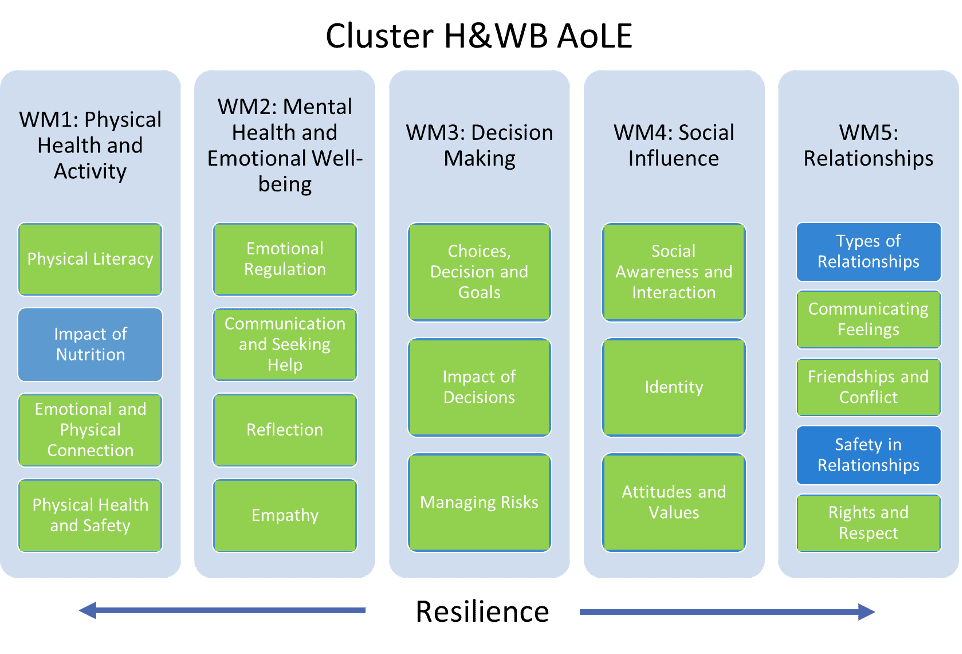

Figure 1 – Learning themes

Figure 1 illustrates the learning themes agreed with my setting’s primary cluster to ensure shared language and learning experiences. Themes highlighted in green could suggest where existing PE approaches may impact.

As previously stated, many PE practitioners, maybe even those with traditions to preserve, might look at the What Matters Statements and progression steps within and use the themes highlighted in green (Figure 1) in WMS 1 (eg. Physical literacy) to justify continuing with well-established curriculum approaches. But a simple exploration of Models based PE (Casey and Kirk, 2021), in this case Teaching Personal and Social Responsibility (TPSR) as the pedagogy of affect, meant themes throughout the WMS were able to be impacted and experienced throughout a unit – all within and through PE. A PE Scholar Concept Curriculum unit was also used to supplement and support the Year 9 boys’ Tchoukball unit because its content (Figure 2) was a natural link to the responsibility levels of the TPSR model.

Figure 2 – Unit from the Concept Curriculum

Figure 3 shows how the unit taught using TPSR linked to and catered for the other WMS themes through experiences without having to resort to “classroom” lessons or a loss of physical activity time. If anything is to be taken from this blog post, it would be this – small changes can have big impacts[MT1] . By ensuring a holistic approach to your lessons and assessment, planning for the AOLE becomes a lot simpler. A lot more impactful.

Figure 3 – Green themes identify those experienced through experiences afforded using the TPSR model.

Teaching Personal and Social Responsibility (TPSR)

The TPSR model is nothing new; Don Hellison first developed the model in the 1970s while working with at-risk youths. The purpose of the approach, as explained on the TPSR Alliance website is to “help students develop themselves as people, learning to be responsible for the ways they conduct themselves and treat other people. Physical activity is used as a vehicle to teach students various life skills that they can practice in the gym and transfer to other settings such as school, community, and home life”. Sounds a bit like the aims of the Health and Wellbeing AOLE and its What Matters Statements – does it not? Or, as Kirk (2010, 2021) calls it – a pedagogy of affect.

The model itself comes in 5 levels of responsibility that students aim to achieve – 6 if you include level 0 (the non-participant) – but, controversially, I tend not to inform students of that level. I make of point of displaying the levels of the model to my class so that they can refer to them. Figure 4 shows the simple graphics placed on the board in the gym throughout the unit.

Figure 4 – Levels of the TPSR model displayed in the sports hall

Essential to the delivery of a unit through TPSR are the key features of lessons:

- Relational Time – informal interactions that create welcoming environments that strengthen personal relationships between teacher and student

- Awareness Talk – a brief, preferably with input from students, to remind them of the focus of the lesson. In my lessons, this is often the confirmation or negotiation of the Know, Show, and Grow learning criteria.

- Physical Activity Lesson Time – You know this bit. However, there should be a focus on students being placed in roles of responsibility.

- Group Meeting – an opportunity for students to discuss learning, evaluate progress, and provide feedback in a safe environment.

- Reflection – a chance for students to reflect and even record thoughts on their own progress, values, attitudes, and behaviours shown during the lesson.

Should you wish to know more about implementing the TPSR model or indeed any other model, I’d direct you to Casey and Kirk (2021), or if you want learn how to implement it within a curriculum, I would direct you to the PE Scholar Curriculum Design course – a significant and possibly career moulding CPD.

Enacting TPSR

For the sake of reading time, I am not going to break down the minutia of the SoW. However, I will show some visual records from the lessons that demonstrate how students engaged in the concepts, responsibility levels, and features of meaningful PE, and thus engaged with wider aspects of the Health and Wellbeing AOLE What Matters Statements. Figure 5 shows a lesson early in the unit, a lesson aimed at responsibility levels 1 and 2, focusing on the rights and responsibilities of others and self-motivation. The Concept Curriculum theme was etiquette. Within this lesson, students were able to devise passing and shooting drills in groups of 4 with the aim of creating scoring opportunities. During the activities, I afforded students chances for group meetings to discuss progress and agree on what would come next. The CC theme of etiquette during drills and discussion becomes very important in respecting the rights of the self and others to play and be active in a socially-safe environment. Whereas persisting with tasks agreed upon as a group required levels of self-motivation. I used relational time during lessons to engage in conversation with students, not only to refocus where required, but also to develop knowledge and rapport – showing an interest in the person beyond the lesson at hand. The characteristics of etiquette, provided by students during the warm-up phase of the lesson, become the success criteria by which they judge their ability to respect others and themselves. A key part of this was giving students the responsibility of devising the rules they wished to play their games with. This allowed students the agency and autonomy to ensure the lesson was enjoyable and at the right level of challenge through group negotiation – features of meaningful PE – despite the fact that official Tchoukball rules were not being used. Besides, the lesson was about working together to develop scoring opportunities through accurate passing and catching – not how to become an elite Tchoukball player.

Figure 5 – The whiteboard from an early unit lesson

Reflection periods were facilitated at the end of each lesson, where students considered the Know, Grow, Show criteria and what they believed they would need to work on next lesson.

Impact

As lessons passed, the learning and personal qualities explored and tempered in previous lessons became visible. As well as increased physical competence in the skills required for the games and increased levels of physical activity, it was also very apparent to anyone walking past my lesson that behaviours, attitudes and relationships were changing. There was a calmness to the lessons, but also a tangible excitement about what was to come.

Students would get changed rapidly and set up equipment without being asked. If a student arrived from the changing room late, another student would pull them up on it before I was able to. Students were setting up relevant warm-up tasks and not picking up equipment until actions were agreed upon and decided. Students were actively asking others, whom perhaps they did not usually work with, to join them – a fully inclusive attitude regardless of friendship or status.

By the final week of the unit, these moments had become established features of the lesson. Many students adjudged themselves to be working within level 4 (caring for others) when discussing their attitudes, emotional responses and typical behaviours. PE lessons had a different feel – a better feel.

Figure 6 – The board at the end of the culminating lesson.

The final lesson of the unit (Figure 6) really demonstrates what had been absorbed by students. Student understandings and interpretations of the CC themes were listed on the board, and most importantly demonstrated practically and in behaviour throughout. Rules for the culminating festival were decided, increasing the number of allowed passes to increase inclusivity and active participation. Students began to reflect on their progress throughout the TPSR levels and on their experiences against the features of meaningful PE (Figure 7).

Figure 7 – Students recording their experiences against the features of Meaningful PE.

The most exciting thing for me as a PE teacher during the final lesson was that all I did was write on the board. The lesson was student-directed, student-paced, and possibly the most enjoyable lesson I’ve ever taught.

Key Questions

- What, if anything, has changed in your PE provision to meet the learning experiences in the What Matters Statements of the Health and Wellbeing AOLE?

- Are your students making holistic progress in your PE lessons? How do you know?

- What are your concerns for PE in the Curriculum for Wales?

References

- Casey, A. and Kirk, D. (2021) Models-based practice in physical education. Abingdon: Routledge

- Kirk, D. (2010) Physical Education Futures, London: Routledge

- Kirk, D. (2021) Precarity, the health and wellbeing of children and young people, and pedagogies of affect in physical education-as-health promotion [Online] Available at: https://pure.strath.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/131075429/Kirk_ED_2021_Precarity_the_health_and_wellbeing_of_children_and_young_people_and_pedagogies_.pdf [Accessed 25 Oct 2022)

- Imsporticus (2023) Traditions not traditional [Online] Available at: https://drowningintheshallow.wordpress.com/2023/07/09/traditions-not-traditional/ [Accessed 19th June 2023]

Further information on student wellbeing

At PE Scholar, we help you stay up-to-date and informed on best practice in Physical Education. The resources and insights below are provided to help you support your students with their wellbeing.

Tracking students’ self-perceptions of wellbeing resource

New wellbeing curriculum for secondary schools resource

Time to RISE Up: Supporting Students’ Mental Health in Schools book

Encouraging students to check-in with their mental health and wellbeing podcast

‘Five Ways of Wellbeing’ insight

Why sleep is essential for wellbeing insight

Trauma-informed PE insight series

Responses