by Kat Jones, Podium Analytics

Healthy adaptation is a core pillar of growth and development for young people. When the body has time and right stimulus to adapt healthily to change, participation across physical education (PE), school sport, and physical activity can be made more enjoyable, with the added benefit of a reduced risk of preventable injury.

Defining Adaptation and Workload

Adaptation

The Specific Adaptation to Imposed Demands (SAID)[1] principle states that the body will adapt specifically in response to the demands and stressors placed on it, and progressively adjust to increasing or decreasing demands. Adaptation requires a load (often referred to as workload, demand or stimulus) to trigger a specific change. These might be from the world of sport or something external; for example, my colleague Glenn Hunter always describes the hardening of skin on our feet – a biological adaptation that occurs when the foot experiences pressure, and it hardens for protection.

Workload

As we know, ‘workload’ refers to the amount of increased effort that the body is challenged to deliver in relation to an imposed demand, and this increased effort provides the stimulus to promote adaptation. It can be defined as: ‘The amount of work, in the context of movement and physical activity, to be done in a specific period of time which is sufficient to produce adaptation’. It’s a relatively simple principle. For example – without training, you likely wouldn’t cope with running a full marathon tomorrow. However, after an extended period of progressive physical and mental workload, you could have adapted to the increasing demands over several weeks well enough to be ready to participate when the time came.

Photo by Clique Images on Unsplash

Workloads required to stimulate adaptation happen universally and can be seen across all contexts. For example, in elite sport, the exact workload required for physiological adaptation can be determined by using multiple science-based strategies which capture aspects such as distance travelled (GPS), speed (timing gates), physiological response to workload (lactate and saliva testing) and psychological factors (psychological load scales). These approaches are all focused on providing information on ‘how much workload is enough’ to promote healthy adaptation and performance adaptation without causing harm or leading to overtraining.

Adapting through physical activity

In an everyday context, it’s of course not so simple nor necessary to capture this level of information to healthily adapt physically. Most of us do it at a level we are comfortable and interested in, for example, using fitness and phone trackers such as Apple watches and Whoop bands to capture information on how our bodies respond to the activities we take part in. If following a specific programme of training, this data can help to manage progressive overload and avoid overtraining.

Biologically, adaptation affects multiple systems in the body resulting in physical, physiological and psychological changes relating to the context you are working in. These are specifically impacted by the relevant physical activity or sport and the associated changes in strength, power, endurance, aerobic and anaerobic capacity, motor skills, or psychological resilience.

Beyond this, adaptation is a key part of developing physical and mental skills that set us up for life and can support positive, lifelong relationships with physical activity and movement.

Promoting physical activity through healthy adaptation in Physical Education (PE)

How can this enable my pupils to thrive in and through the PE Curriculum?

We know that there are decreasing activity levels in young people, with fewer than half of children and young people taking part in 60 minutes of physical activity a day.[2] As children and young people learn and develop throughout physical education, their bodies are constantly adapting and finding ways to cope with new demands placed upon them.

Covid-19

Covid-19 rippled through the education and physical activity sector, with significant impact on physical and mental health and social interaction in children and young people. As pupils returned to school in September 2020, the Youth Sport Trust surveyed PE and schools leads and found that almost three quarters of teachers reported children returning with low levels of physical fitness and almost half noticed mental wellbeing issues. [3]

Impacts of physical inactivity

For those who aren’t moving enough or engaging in physical activity sport, getting healthy adaptation right is crucial. Doing too much too soon, physiologically and/or psychologically, can result in injury or adverse experiences and, in turn, impact someone’s lifelong relationships with physical exercise. For example, if adaptation isn’t managed well, such as too little workload or a lack of stimulus followed by a period of an increased ‘dose’ or demand, injury is more likely to occur. The physical knock-on effect is clear but socially, our understanding is that it can also lead to drop out of sporting activity and further impacts.

Growth and Maturation – The Developing Child

This potential social impact applies particularly to 11–18-year-olds who, in addition to the activity-based adaptation, experience another form of natural adaptation from the growth spurt. This accelerated period of growth means that as the body grows, various systems are less able to adapt, making them more vulnerable to different types and application of workload. For your pupils, going through the growth spurt means they will be adjusting to their new body size and shape. This can create movement skills gaps and potentially reduce their confidence in being physically active, increasing susceptibility to physical injury.

Adapted physical education for adolescents

Dr Gemma Parry is leading great work on the impact of adolescent physical development with Podium Analytics and the University of Bath and you can read her blog post here. In her current research project on the Developing Child, Gemma is providing an educational series for PE teachers and sports partners on the potential knowledge gap around the adolescent growth spurt. In one of her modules she writes:

Making appropriate adaptations to curriculum and content for developing children and adolescents is crucial to mirror the adaptations of their developing bodies and minds, enhancing enjoyable participation and safer practice.

So, what can I take away from this?

My experiences and role at Podium Analytics enable me to look at the world through an injury-prevention lens, advocating for healthy adaptation as a core principle to enable children and young people to enjoy physical activity and minimise the risk of injury.

Providing adaptive PE classes and the least restrictive environment

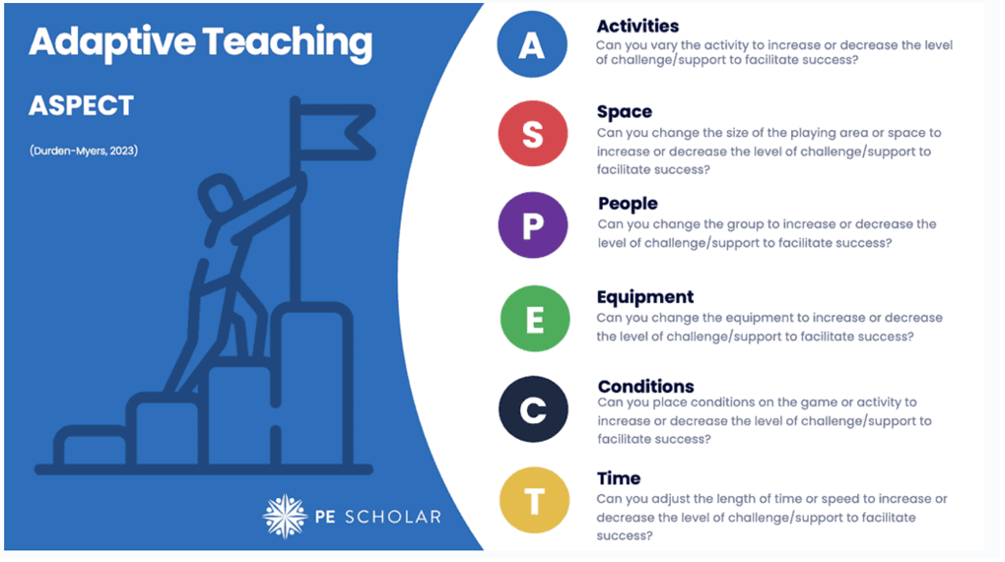

Adaptive Teaching is a similar principle described in pedagogy, which seeks to provide more inclusive experiences and suggests that all pupils are provided with the same learning objectives, but with varying levels of support based on individual needs, such as prior experience or learning styles.[4]

This recognises whether the workload – be it an activity, learning or social interaction – can be altered to cater for individual needs and by making small changes to the same activity, to achieve the same goal or teaching outcome.

The STEP approach to adapted physical education

Dr Liz Durden-Myers writes a brilliant piece that illustrates the difference between differentiation and adaptive teaching and how it supports the learning and inclusivity in PE. You can find this here. The STEP approach[5] is one which is widely used, and uses Space, Time, Equipment and People to make adaptations that support and stretch individual learners.

Author: Durden-Myers, 2023[6]

Empowering your pupils through quality physical education

You will know from the students you teach that each one is brilliantly unique and equally challenging. Exploring the ways in which you can support healthy adaptation through the time they spend with you in PE or school sport can help embed positive relationships with movement and physical activity.

With the update of the School Sport and Activity Action Plan in July last year, the Department for Education set out to support senior leaders and teachers to provide high quality PE and sport for at least two hours a week. [7] For some, this short amount of alone may not be sufficient to promote and nurture healthy adaptation; however, fostering positive experiences in and through activity, unlocking and upskilling young people in the activities they enjoy, can inspire lifelong participation and empower them to seek continued relationships with physical activity and sport.

If you’d like to talk in greater detail about this, please contact Kat Jones (kat.jones@podiumanalytics.org).

PE Scholar also provides a bite-sized course on models-based practice, which includes the STEP principle and adaptive teaching. Click here to find out more

Acknowledgements

Theory supported by Glenn Hunter and Dr Gemma Parry, review by Anna Berry – Podium Analytics

[1]https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803100522144?p=emailACuEokVfrjafA&d=/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803100522144

[2] https://www.sportengland.org/news-and-inspiration/childrens-activity-levels-hold-firm-significant-challenges-remain

[3] https://www.youthsporttrust.org/media/2h0fqf5z/returning-to-school-after-covid-19.pdf

[4] https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1083517.pdf

[5] https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17430437.2016.1225882

[6] https://www.pescholar.com/insight/adaptive-teaching-in-pe/#:~:text=Adaptive%20teaching%20in%20PE%20is,individual%20needs%20of%20all%20students.

[7]https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/64b7c813ef5371000d7aee6c/School_Sport_and_Activity_Action_Plan.pdf

Responses